Finding flow in a new skill or advancing in a current skill will always begin with facing a level of resistance. This resistance or pressure is a must, it's needed for flow. It is the thing that is hiding flow from you. Understanding that this veil is hiding the truth of the skill from you will allow you to reframe the ‘resistance’ into opportunity. But what if this resistance creates or triggers a sense of relieving a fearful behavior? Reframing the resistance might not be enough to overcome this stressful struggle that you know somehow you need to find a way through… This tidal wave of emotions floods your system as frustration. This prompts your inner critic to grab the microphone and walk onto the stage of your mind to begin the roasting.

“If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat.”

Sun Tzu - The Art of War.

For us to know the enemy a bit better we must understand what our stress response system is up to during all this resistance facing.

When your senses detect a threat they send information straight to a key area of your brain that contributes to emotional processing called the amygdala. When it deciphers the signal as the threat it sounds the alarm and instantly sends a signal to the hypothalamus. Your hypothalamus is like your HQ (headquarters) transmitting communications throughout the rest of the body via the nervous system so that the person has the energy to fly or run.

Your Hypothalamus (HQ) uses two components of your autonomic nervous system like a gas pedal and a brake in the car. The gas would be your sympathetic nervous system (fight, flight, or freeze) whereas your parasympathetic nervous system would be your brake or as I like to say taking your foot off the gas. These actions control body functions such as breathing, blood pressure, and heartbeat, dilating and constricting blood vessels.

At first, the amygdala yells to the hypothalamus to release SAM. I know, ‘release SAM’ sounds like a hit man. SAM stands for Sympathomedullary Pathway (sympathetic - adrenal medulla. The middle or inner layer of the adrenal gland). The sympathetic nervous system is triggered into action when the hypothalamus sends a message to the adrenal medulla ordering the release of epinephrine (adrenaline) into the bloodstream. The second adrenaline (epinephrine) hits the bloodstream a number of physiological changes begin to take shape. Your heart beats faster than normal, pushing blood to the muscles and your organs. Breathing begins to quicken in conjunction with your bronchiolitis (small airways) opening wider. This increase in oxygen intake increases alertness. Sight, hearing, and your other senses become heightened. As this is all happening, adrenaline (epinephrine) triggers the release of stored blood sugar (glucose) and fat so that your system has the energy to address the perceived threat at hand.

All this happens before your brain’s visual areas have the chance to process what just happened. This is why people appear to have some sort of ninja-like sense in times of extreme danger

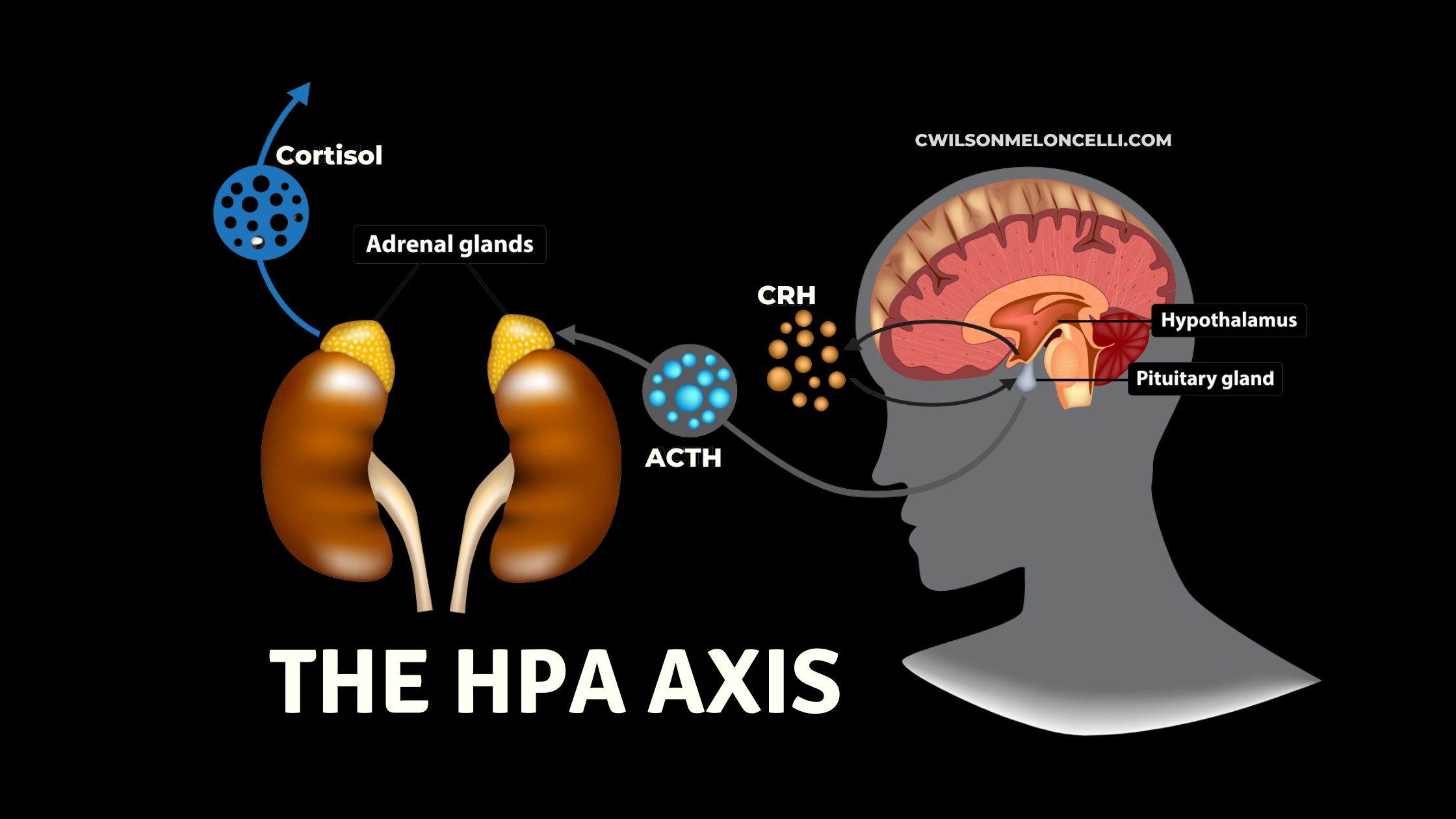

As all this has been going on the hypothalamus has also set in motion the HPA axis. The hypothalamus, pituitary, and adrenal glands. This time the outermost layer of the adrenal gland is employed.

As the boost of adrenaline (epinephrine) begins to lessen, the HPA axis releases a series of hormones to keep the foot on the gas of the sympathetic nervous system. The HPA axis changes into another gear when that perceived threat is still present. The hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) travels to the pituitary gland, which in turn triggers the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which then is delivered to the outermost layer of the adrenal glands to promote the release of cortisol. This keeps your system on red alert. All senses are heightened breathing and heart rate are maintained at a high level. Once the threat has been removed your cortisol levels drop, your parasympathetic nervous system takes the foot off the gas pedal and the stress response quietens.

Our stress response is a natural response to danger that has served and protected us. With the boost of adrenaline that increases the heart rate, breathing evaluates our blood pressure and boosts our energy supplies. This quick acceleration and extra pressure on our blood vessels require immediate repair. Then comes cortisol to clean up the damage. This stress hormone helps release more energy while increasing the availability of substances that repair tissues. Cortisol also curbs functions that would be nonessential during the fight, flight, or freeze situation, helping focus energy on the essentials required to fight or flight. The areas that are suppressed are, our digestive system, reproductive systems, immune system, and growth processes. This natural alarm system sends morse code to the limbic system that controls mood, motivation, and fear.

Once the perceived danger is passed adrenaline and cortisol levels drop, your heart rate, and blood pressure return to baseline levels and your other systems return to normal functioning. However, traumatic experiences can leave emotional scars that could reopen through internal and external mental triggers. That can create a mental replay of the event of fear, causing the stress response to take action. Others don't do this or are unaware that it happens. Along with these potential repetitive steps, some stressors are always present and you constantly feel under attack, therefore your stress response (sympathetic nervous system - fight, flight, or freeze) is left running.

This happening along with the tap of cortisol and other stress hormones leads to chronic stress. Signs that your tap of cortisol has been running are things like: Anxiety, depression, digestive problems, headaches, muscle tension, muscle pain, heart disease, high blood pressure, sleep problems, weight gain, poor memory, and concentration wavering.

Here is what you can do to take control.

When you become aware of the threat, danger, or stressor, you now know that your SAM (Sympathomedullary Pathway) has already started and adrenaline (epinephrine) has now triggered your sympathetic nervous system into action. Your parasympathetic nervous system activation will help calm your system down and regain control of your fight or flight response (assuming the threat is not life-threatening).

Here’s a trick. Your breathing is the best control you have because when you breathe in this has a sympathetic response and when you breathe out you have a parasympathetic response. We know that a sign of the sympathetic nervous system is fast breathing, so we can slow our breathing down by extending our exhale purposely activating more dominant parasympathetic breathing. This is accompanied by utilizing nasal breathing which stimulates a greater amount of nasal nitric oxide into your system. Nitric oxide is a vasodilator. A vasodilator opens up your blood vessel adding better oxygen function.

So, the technique would be 2secs inhale 4-6seconds exhale, all performed with nasal breathing. With the objective of performing it without tension in your body. If you feel tension shorten it to 1sec -3sec. The principle is you have a longer exhale.

One other exercise you can implement consciously is the physiological sign, your body already does it naturally throughout the day. This simple exercise was discovered in the 1930s to help regain control quickly of the build-up of stress. The physiological sigh was re-energized to the public by Dr. Andrew Huberman professor in the Department of Neurobiology at Stanford University, who highlights that this is something we do involuntarily on average every 5 minutes including the moments before we fall asleep, during sleep, and when we cry. This translates into 12 sighs per hour.

UCLA professor of neurobiology Jack Feldman points out that the reason we sigh is to inflate the alveoli, the half-billion, tiny, delicate, balloon-like sacs in the lung where oxygen enters and carbon dioxide leaves the bloodstream. When the alveoli collapse, as they do, they compromise the ability of the lung to function correctly by exchanging oxygen and carbon dioxide. Feldman points out that the only way to pop them open again is to sigh. Which doubles the volume of a normal breath and makes the body feel more relaxed.

The exercise is, 2 short quick inhales through the nose, with one long exhale through the nose. This translates very similarly to the previous exercise of the short inhale and the long exhale. Sympathetic and parasympathetic stimulation.

The great thing about these methods is that you use your body to control your mind, rather than trying to use your mind to control your mind. If you try the latter, you will only feed the fire of fear and stress.

This is how you can overcome the resistance and reframe the struggling in opportunity!